AG INSIGHT | 07/12/2017

More than red tape: environmental regulations can drive growth

Nick Molho, Executive Director at the Aldersgate Group, argues that, while often portrayed as a barrier to growth, well-designed environmental regulations can in fact result in a range of positive economic outcomes.

This blog is part of series published around the launch of an Aldersgate Group commissioned report by BuroHappold Engineering Help or Hindrance? Environmental regulations and competitiveness.

Often portrayed as a barrier to growth, well-designed environmental regulations can in fact result in a range of positive economic outcomes. The UK government recently published its Industrial Strategy White Paper and Clean Growth Strategy. In them, the government sets out commendable ambitions on increasing the use of clean energy, improving energy efficiency and cutting transport emissions and waste. The Industrial Strategy also identifies clean growth as one of the UK’s four “Grand Challenges”, with a clear intent to grow UK supply chains across the low carbon economy.

Regulations have a role to play in delivering these objectives, yet they have often been portrayed in the past as a drag on growth, talked about in the context of “cutting red tape”. Today, the Aldersgate Group publishes a report from engineering consultancy BuroHappold looking at the impact of existing environmental regulations on businesses and what lessons can be learnt as the government begins the task of delivering on major environmental and industrial commitments.

From buildings and waste to the car industry

The report is based on business interviews exploring the impacts of the London Plan on the construction industry, the Landfill Tax on the waste industry, and the EU emissions standards regulations on the car industry. In all three cases, it concludes that on the whole environmental regulations have delivered positive economic outcomes. The compliance cost attached to each regulation is offset by benefits flowing from greater business investment in innovation and skills, better performing products and infrastructure and greater competitiveness such as through leadership positions in new markets.

In the construction sector, the carbon emission reductions mandated by the London Plan have triggered significant investment in innovation and skills in the design and consultancy parts of the supply chain. An estimated 4,000 jobs have been created as a result of the low carbon infrastructure (district heating and renewables) delivered under the Plan for planning applications in 2015. The London Plan and UK design and consultancy firms are seen as setting the benchmark for energy efficient buildings globally.

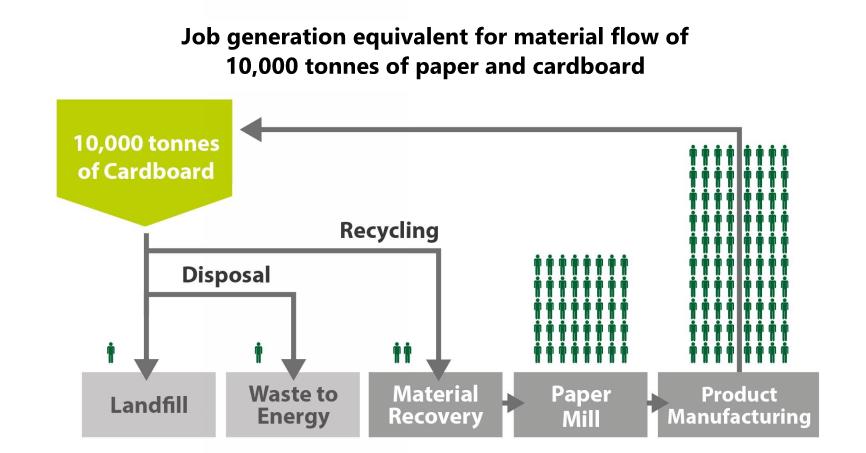

By gradually increasing taxation on the landfilling of waste, the Landfill Tax is one of the key drivers that resulted in the waste industry investing in the provision of new services and infrastructure, such as recovery, sorting and recycling facilities, with significant job creation attached to it (see diagram below). It has done so whilst cutting the tonnage of waste sent to landfill in the UK by some 72 per cent in 20 years.

Photo by BuroHappold Engineering

In the car industry, where the UK supply chain is in a much better shape than it was ten years ago, the challenge to comply with the EU’s gradually tightening emissions standards has been technically and financially significant. It has however resulted in huge investment in research, development and skills in European and global supply chains as well as job creation. Globally, automotive companies rank third in terms of investment in research and development.

Lessons for good policy making

There is obviously such a thing as good and bad regulation and all the regulations studied as part of this report have their flaws. The London Plan has delivered much progress in the energy efficient design of buildings but there is a big performance gap between what the designers are proposing, what contractors have the skills to deliver and how buildings end up performing in practice. This is partially down to broader government policy needing to tackle the lack of skills in contractor businesses as well as the London Plan putting too much focus to the energy efficiency of buildings at the design stage rather than when they are actually in use.

The Landfill Tax has in some ways been the victim of its own success, with evidence of increasing illegal waste disposal and some businesses shipping British waste to other EU countries where there is an overcapacity of incineration facilities. In the car industry, the VW scandal shed light on the inadequacy of the emissions testing methodology, which failed to replicate real world driving conditions and undermined the credibility of the EU emissions standard regulations for passenger cars.

The successes and flaws of existing regulations hold some valuable lessons for the future. To maximise economic and environmental benefits and to avoid unintended consequences, well-designed regulations need to comply with some key principles. They need to be pitched at the most effective geographic scale (regional, national or local), provide a clear sense of direction, be compatible with existing policies, be implemented in a way that gives businesses a chance to adapt and be complemented by other initiatives such as skills development, regulatory enforcement or support for businesses that are at risk in the transition to a low carbon economy.

The challenges ahead

Going forward, all three industries and policy areas studied in the report face important challenges. The energy efficiency of the UK’s buildings needs to be radically improved in the near future to meet climate targets, which makes solving the current weaknesses of regulations like the London Plan and setting clear national ambitions on building energy efficiency urgent. What used to be a discussion on waste now needs to be about significantly improving the resource efficiency of the economy, by encouraging better product designs and encouraging material re-use.

In the car industry, the global shift to more autonomous and electric vehicles is likely to reduce vehicle complexity, meaning that fewer jobs are likely to be required in automotive engineering, with more jobs being created to deliver the needed in-car connectivity, charging and energy storage infrastructure. The UK government and the car industry will need to continue working closely together through the likes of the Automotive Council to put the UK supply chain in as competitive a position as possible in this transition.

With 447,000 people employed and a turnover of around £77bn in 2015, the UK’s low carbon economy is off to a good start. However, in a context of fierce global competition to provide low carbon goods and services and the need to address pressing environmental challenges, well-designed regulations will be essential to build on this progress and deliver the government’s clean growth ambitions.

Nick Molho is Executive Director at the Aldersgate Group

———

Our report with BuroHappold here: Help or hindrance? Environmental regulations and competitiveness